Even more fascinating when they’re dead

Whales are among the world’s most magnificent, fascinating creatures. For UH Mānoa doctoral student Emily Young, however, they become far more interesting when they die, sinking to the ocean floor to become food for thousands of animals. At first, each “whale-fall” looks as one might expect: attractive to sharks, shrimps and other scavengers. Then, long after the meat has been picked from the skeletons, the bones themselves are home to worms, clams and microbes who have evolved just to live on these bones.

“These microbes now form the base of the food web, an environment that can last up to 70 years,” says Young, who examines the bones to learn “who’s eating whom” and how the populations around whale falls vary across ocean depths and locations.

Hooked on alien-like creatures

As an undergrad at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom, Young took a deep-sea biology course. “It got me hooked,” she says. “I love the idea of weird, alien-like creatures in the deep sea. There was a lecture about whale-falls, and I couldn’t believe there were all these species evolved to live on these habitats. How does that happen?”

Young wrapped up her master’s studies and sent an email to Dr. Craig Smith, the UH Mānoa professor of oceanography who first wrote and hypothesized about whale-falls. “I’m finishing my master’s,” she wrote. “If you have anything coming up, I’d be really happy to work with you.”

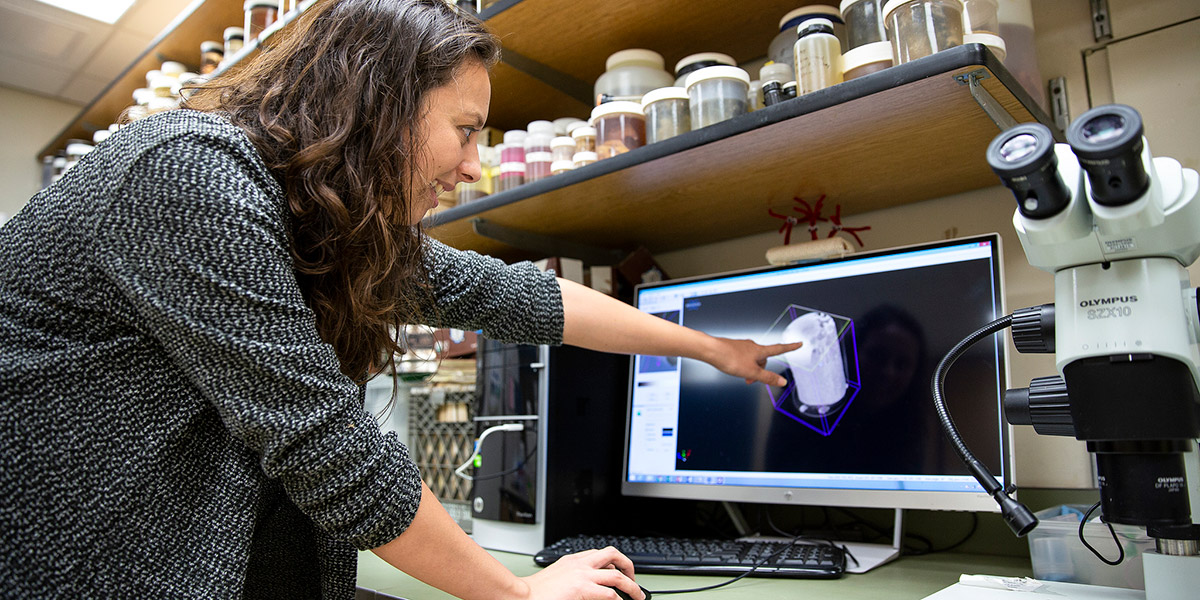

Within two weeks of earning her degree, she was in the United States for the first time, a Mānoa PhD student on a boat in the northern Pacific Ocean, retrieving the whale bone Smith’s team had placed there fifteen months earlier. Emily now spends most of her time in the lab, sorting and identifying the tens of thousands of animals that associated themselves with the seafloor bones.

Denise B. Evans Fellowship: “That final boost”

“Emily has distinguished herself with great progress on an excellent project,” says Smith, who nominated Young for the Denise B. Evans Fellowship in Oceanography. “She’s outstanding in class work, and a good citizen in terms of outreach and education. The committee appreciated her accomplishments, but they were impressed by the full suite of what Emily does.”

Denise B. Evans funded the fellowship as part of her estate. Since 2013, the fellowship has supported graduate students exploring undersea lava flows and populations of phytoplankton, in areas as far-flung as the Galapagos Islands and the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

Young says, “The fellowship has been great for me. It’s freed me up this year, so I don’t have to teach and can focus my time on being in the lab. When I’m sorting these bones, I need hours at a time to make it worthwhile. I’m very grateful for the Evans fellowship for supporting me for a whole year. It’s giving me that final boost I need to finish this research, pursuing what I’ve always wanted.”

Questions? / More Information

If you would like to learn how you can support UH students and programs like this, please contact us at 808 376-7800 or send us a message.